With cross-national business collaboration on the rise across the globe (up by 50% or more over the past two decades according to HBR), learning to be a “good” teammate is rife with difficulty, and often drama, when you consider the facts. The accepted approach to teamwork in one place is often quite the opposite for teammates located 6,000 kilometers away or teammates who come from places 6,000 kilometers away. I like to respond to 95% of my emails the same day, but my colleagues in Brazil will often take several days. Japanese colleagues cringe when teammates outside Japan give individual feedback in front of their peers or during group calls. Germans find the boastful sharing of accomplishments and self-promotion on the part of their American colleagues suspect and excessive. The downside to these differences is that they don’t build trust, and as part of a virtual team, trust is a critical cornerstone.

By accepting such cultural differences as a fact of (business) life in 2016, we can turn to a new study by Google that demonstrates how team performance is very much connected to how team members treat each other and not who is on the team.

The New York Times Magazine details the steps Google took to discovering the formula for the perfect, high performing team. The researchers found the following:

“We had lots of data, but there was nothing showing that a mix of specific personality types or skills or backgrounds made any difference. The ‘who’ part of the equation didn’t seem to matter.”

The factor determining team success was all in how teammates interacted with each other, regardless of how bright they were. The two specific patterns that led to success were 1) when members of the team spoke in equal amounts and 2) when members exhibited high levels of emotional intelligence. The researchers called the latter “social sensitivity,” which means that team members “were skilled at intuiting how others felt based on their tone of voice, their expressions and other nonverbal cues.”

These are the makings of psychological safety, which Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson defines as a “shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking…a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up…It describes a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves.’’

Google put all of this information into various charts, graphs and reports, and for a data-driven organizational culture, this made it much easier for Google to debrief and tease out relevant learning.

Here at RW3 CultureWizard, we designed a team profiler called TeamPlace which helps teams create their own guidelines and norms to move towards high performance.

In my experience facilitating team-building workshops, most every team profile I’ve ever debriefed invariably points to best practices like social sensitivity, equality in conversational turn-taking and spending more time face-to-face developing interpersonal trust.

Furthermore, the Intercultural Awareness Model that TeamPlace leverages to analyze work style gaps establishes a common vocabulary for teams to articulate the way they feel about their teamwork, which drives towards the formation of a culture of high-performance.

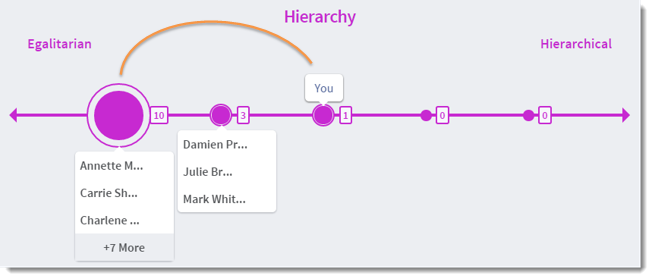

Take the following screenshot of a sample team’s particular distribution across the cultural dimension we call Hierarchy. Note that the “You” bubble is relatively more hierarchical than everyone else on the team. What does this mean? You might be reticent to speak up during a team meeting where senior members are present, or you might defer completely in decision-making to those with more experience despite having your own ideas. All of this comes from your personal cultural value system that tells you it’s more appropriate to do so.

If I were your teammate, and relatively more egalitarian, I’d be able to read through a series of suggestions that TeamPlace presents for how I could best approach my work with more hierarchical members. For example, I could:

• Create detailed agendas identifying who leads meetings, who speaks when, who keeps time and who takes meeting notes

• Schedule 1-on-1 meetings to rehearse contributions or speaking opportunities with more hierarchical teammates who are apprehensive to raise their ideas

• Encourage more egalitarian participants to allow for silence and to be careful with interruptions so that everyone has a chance to jump in

At a minimum, TeamPlace raises awareness of differences between team members, and at a maximum generates a team charter that fosters the levels of innovation and success that global organizations need to thrive.

Coincidentally, one Google researcher corroborates these effects of TeamPlace:

‘‘Just having data that proves to people that these things are worth paying attention to sometimes is the most important step in getting them to actually pay attention. Don’t underestimate the power of giving people a common platform and operating language.’’

How are you working towards a psychologically safe team environment? What other factors or best practices can contribute to this optimal environment? Want to learn more on working successfully with your team? Click below to rquest a demo!